Join our next live session with Nacha on modern, programmable ACH on February 12th.Register here →

Fintech Eng Challenges, Part I: Different Balance Types in a Wallet

Learn what balance types mean for a digital wallet product, and unpack the engineering challenges of (and strategies for) keeping them consistent at scale.

When customers open their digital wallet, the “balance” they see can mean several different things, depending on the context. It can represent fully cleared money, authorized but unsettled money, or even remaining available credit for borrowing. Engineers building digital wallets must provide a source of truth for the question: what’s my balance?

Businesses rarely expose raw ledger entries directly to end users. Instead, they compute and surface different balance types depending on the use case. This article explains what balance types are, why they exist, how fintech companies define them differently, and the engineering challenges of supporting them at scale.

What Balance Types Are Needed in a Wallet?

In a ledger database, every transaction is recorded immutably as a debit and a credit. A balance is simply an aggregation of those transactions over time. A balance type defines which subset of transactions count toward that aggregation (e.g., only posted transactions, or both posted and pending).

Wallet balance types are abstractions of this underlying ledger, and they allow systems to answer questions like:

- How much money has fully settled? (

posted_balancehelps internal users for reconciliation purposes) - How much can the customer spend right now? (

available_balanceprevents overspending and failed transactions) - What has the customer purchased recently? (

pending_balancehelps end users see transactions in motion)

Core Balance Types

1. Posted Balance

The posted balance represents transactions that have fully settled. In a wallet product, the posted balance is the basis for reconciliation, the process of matching subledgers to the underlying bank. It reflects the final state of funds.

Formula: Posted Balance = Σ(Posted Inflows) – Σ(Posted Outflows)

Example: Let’s look at a merchant wallet for "TechGear, Inc" on an e-commerce platform.

Posted Balance = 1,000,000 + 284,000 - (175,000 + 8,420 + 2,150) = ~$1.1M

2. Pending Balance

The pending balance includes all money movement, regardless of its settlement status. Pending balances give customers a more up-to-date view of their activity, but are less reliable since some pending items may never post. For example, an inflow funded by an ACH debit on an external bank account may fail because of insufficient funds. On the outflow side, an incidental hold on your card placed at the beginning of a hotel stay won’t ever post and will eventually expire.

Formula: Pending Balance = Σ(Posted Inflows + Pending Inflows) – Σ(Posted Outflows + Pending Outflows)

Example: Let’s look at a business account for “VeryVest,” processing end-of-day activities on an investing platform.

Pending Balance = 1,000,000 + (500,000 + 12,450) - (750,000 + 225,000) = ~$547k. This balance represents authorized but unsettled transactions moving through various clearing networks (e.g., Nacha, Fedwire, Options Clearing Corporation).

3. Available Balance

The available balance is more conservative than the posted balance. While the posted balance includes only posted money movement, available balance subtracts money that’s moving out of the account. This balance is useful when you want to display a spendable balance to customers. You don’t want them to spend money that’s already on the way out, even if that outflow could possibly fail.

Formula: Available Balance = (Posted Inflows) – (Posted Outflows + Pending Outflows)

Example: Let’s look at a property management company "Mod Condo, LLC" holding funds for a rent-based rewards platform:

Available Balance = 1,000,000 + (24,750) - (45,000 + 550,000) = ~$429K. This is how much the property manager can allocate for immediate rewards purchases or owner distributions.

How Wallet Companies Use Balance Types

Fintechs designing wallets vary in their use of balance types. Although almost all have a form of the core balance types above, most wallet providers usually emphasize available balances for UX (e.g., Paypal, CashApp, Venmo are all consumer wallets that expose the available balance as a default). However, even this can vary:

Alternative Balance Types and Calculations

1. One of our fintech-as-a-service (FaaS) customers has a wallet they white-label for their clients. They designed this wallet to have four balance types:

- The usual suspects:

available,pending,posted - And another balance type:

reserved_balance, for earmarked amounts not yet spent (e.g., holds). They differentiate this frompending_balancewhich includes balances awaiting completion.

This design supports wallets that must serve both customer-facing queries and compliance/reconciliation.

2. A fintech firm offering credit building services has a wallet as the user-facing app; they calculate their available_balance with this formula:

Available = Posted Inflows + Pending Inflows + Posted Outflows

In this case, it is calculated nearly opposite to what we’d expect. It’s an optimistic balance: the balance is as large as possible (i.e., once the payment is initiated, they want to show the available balance going back up immediately). This makes sense for this company that is focused on credit-building and manipulating the customer-facing metric to help improve credit profiles.

3. For wallets that are the user-facing application of a lending or credit product, balance types often include credit limits or remaining spend capacity.A credit limit can be calculated as: Available Credit = Credit Limit – Available Balance. The Available Balance represents what a customer owes, so subtracting it from the Credit Limit gives back how much purchasing power the customer has left.

These are just a few examples of how balance types will vary across businesses, and why it’s so important to accurately chart and model accounts, as varied definitions can increase engineering complexity. The most important thing to optimize for is customer trust: wallets need to show balances in a way that matches expectations.

Engineering Challenges With Multiple Balance Types

1. Atomicity and Consistency

When a transaction posts, multiple balances (posted, pending, available) need to update together. If only one updates, the system drifts out of sync.

If the second query fails (e.g., network blip), posted ≠ available. The ledger remains correct, but balance views are inconsistent. This risk multiplies under high concurrency, as many tries are going through at once. Failed payments = bad UX.

2. Balance Drift

Cached balances may drift from true ledger values if writes fail or reconciliation lags (e.g., if the available balance shows as $5,000, but in reality it is $4,750 due to a missed pending entry). This can immediately break trust.

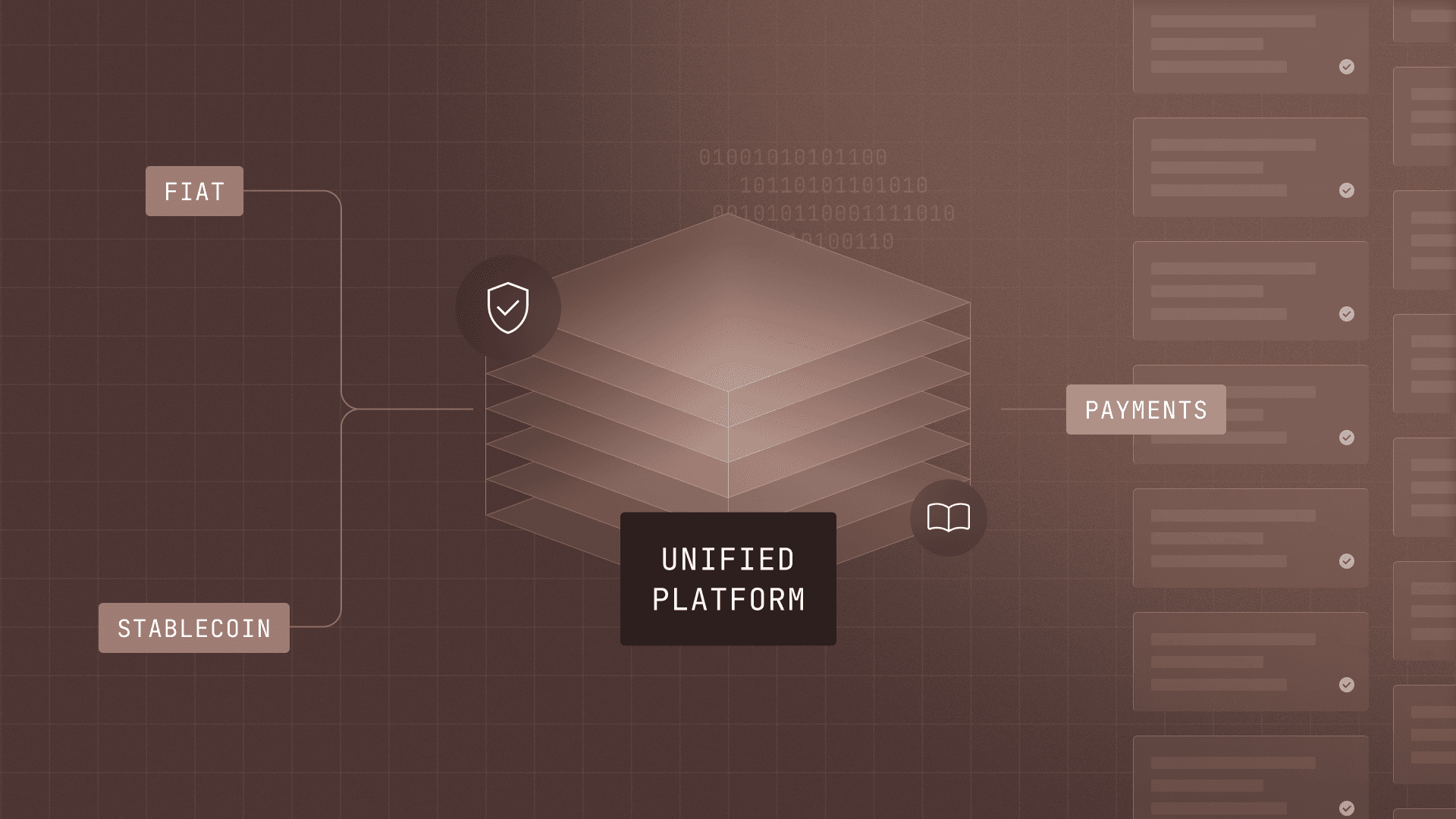

3. Multi-Currency Wallets

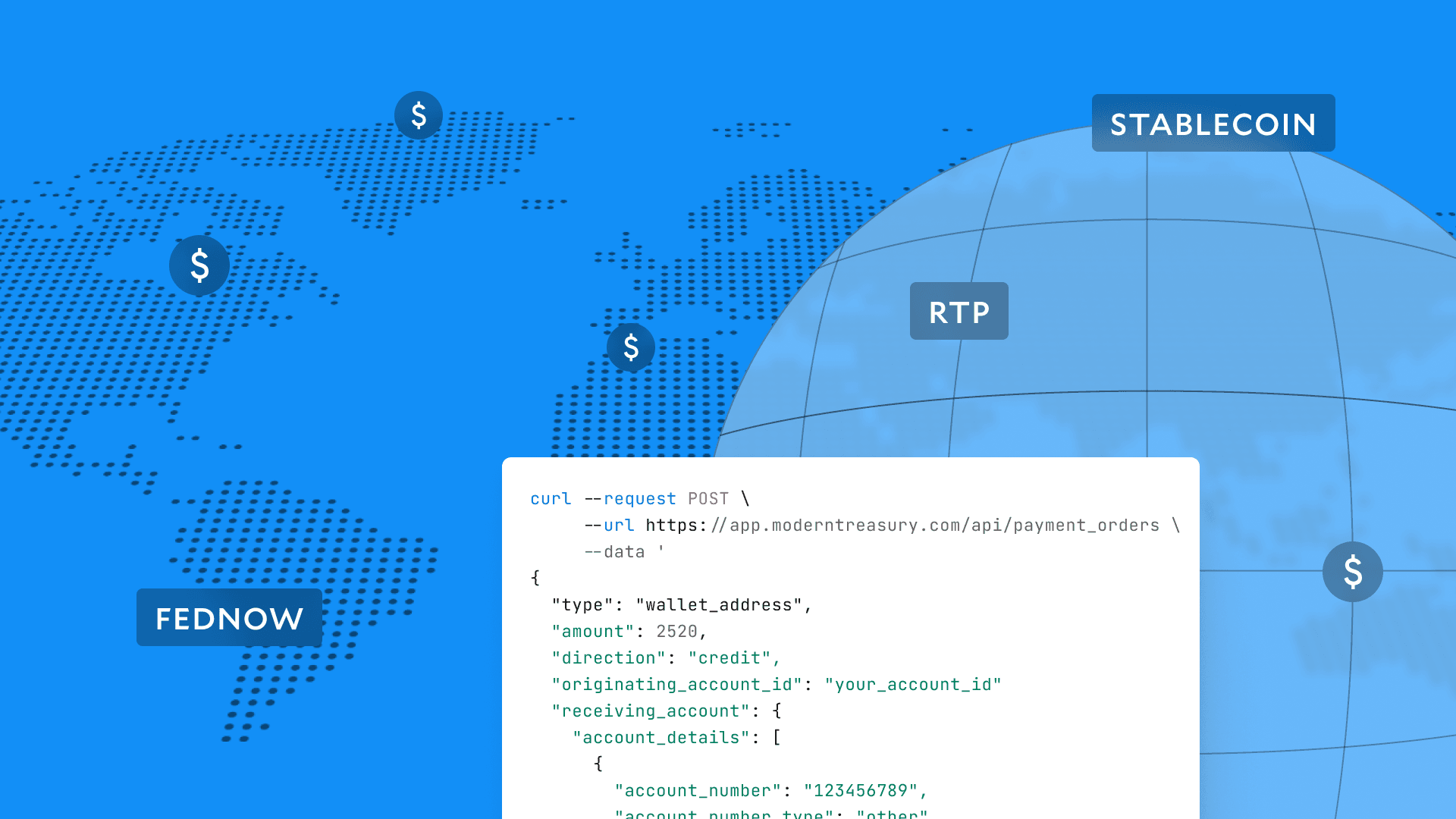

Customers and partners have the same rapid response expectations for their wallets, even with added complexity of multi-currency (e.g., stablecoins or foreign currency). This means balances need to be tracked for each currency separately, with FX conversions as a snapshot for total wallet balance calculations.

Strategies to Address These Challenges

- Always anchor balances to a ledger: Keep balance logic modular: ledger = source of truth; APIs = interpretation layer. Document balance definitions explicitly for end users and developers.

- Strong Ledger Guarantees: Use immutable, double-entry transactions to ensure every balance calculation has a solid foundation.

- Locking and Versioning: Apply mechanisms like

lock_versionon ledger writes to avoid race conditions. Use pessimistic logic to help prevent failed transactions. - Balance Caching with Reconciliation: Cache balances for performance. Periodically reconcile against the ledger to detect drift.

- Flexible Balance Objects: Expose balances through structured APIs (e.g., Modern Treasury’s Ledger Balances), allowing different balance views to coexist. For lending wallets, define clear rules (e.g., what counts toward available balances and how limits interact).

If you’re designing a wallet, don’t treat “balance” as one field. These definitions shape customer trust. Getting them right means preventing failed payments, ensuring compliance, and enabling new products to thrive. Some tips for the road:

- Define your balance types up front.

- Document posted, pending, and available balances.

- Decide which are customer-facing vs. internal.

- Tie balance updates to immutable ledger entries.

- Never update balances independently of transactions.

- Use database transactions to keep posted, pending, and available balances consistent.

- Plan for drift detection.

- Build reconciliation jobs that compare cached balances against the ledger.

- Alert on any mismatch. Even better, turn off caching as soon as a mismatch is detected.

- Expose balances clearly in APIs.

- Name fields explicitly (

available_balance,pending_balance, etc.). - Link to docs that explain exactly how each is calculated.

- Name fields explicitly (

Conclusion

Multiple balance types are a necessary feature of wallets, but supporting them introduces challenges for engineers. Each definition solves a real business need, but only when implemented carefully.

Start by mapping which balances your wallet needs today. Then, build your schema so that adding new balance types later won’t require a rewrite. The challenge is to make sure your underlying ledger can scale across balance definitions without sacrificing reliability. We’ve done it, so we can help. Read our full documentation or reach out to us.

Lucas Rocha is the PM on the Ledgers product, driving strategy for the company’s database for money movement. Before Modern Treasury, Lucas worked in VC at JetBlue Technology Ventures and Unshackled Ventures. He earned his MBA from Harvard Business School and his bachelor’s degree from Northeastern University.