How Risky is Sitting in the Flow of Funds?

When a business sits “in” the flow of funds, it means that money will, at some point, pass through the business’ bank account. This primer digs into funds flow models and the risks and benefits associated with sitting in the flow of funds.

Introduction

Let’s start with a definition. The “Flow of Funds” is the movement of money between two or more bank accounts. Flows can vary depending upon the number of times money moves, the currency, the payment rail, type of business, the goods or services the business provides, by whom the business is run, and asset types that the business holds.

Aside from cash, when money moves, it always moves from one bank account to another. The flow of funds is composed of one or more “hops” of money between bank accounts. These accounts may be owned by you, a third-party processor (TPP), customer, vendor, and so on. The flow of funds is a common way to understand a business and model its payments risks.

When you hear a business is “in” the flow of funds, this means that at some point, one of those hops is the business’ bank account. However briefly the money may sit in the business’ account, they are now “touching the money,” which means they have some liability and risk.

It’s important to define what “risk” means in the context of flow of funds. Similar to credit cards, risk presents itself in generally two common ways: regulatory and fraudulent. Regulatory risk may mean something like complying to Anti-Money Laundering (AML) rules and regulations.

The risk of fraud is if a customer issues a return (like the “chargeback” in the world of credit cards, a customer may say, “I never authorized this debit”). This risk has many attack vectors and can be costly, but is also mitigated by verifying identities, accounts, balances, and having a simple Compliance program which is tailored to your unique business.

So now, we are left with our ultimate question: How much risk is there when sitting in the flow of funds? Let’s go a bit deeper to see.

Flow of Funds Methods

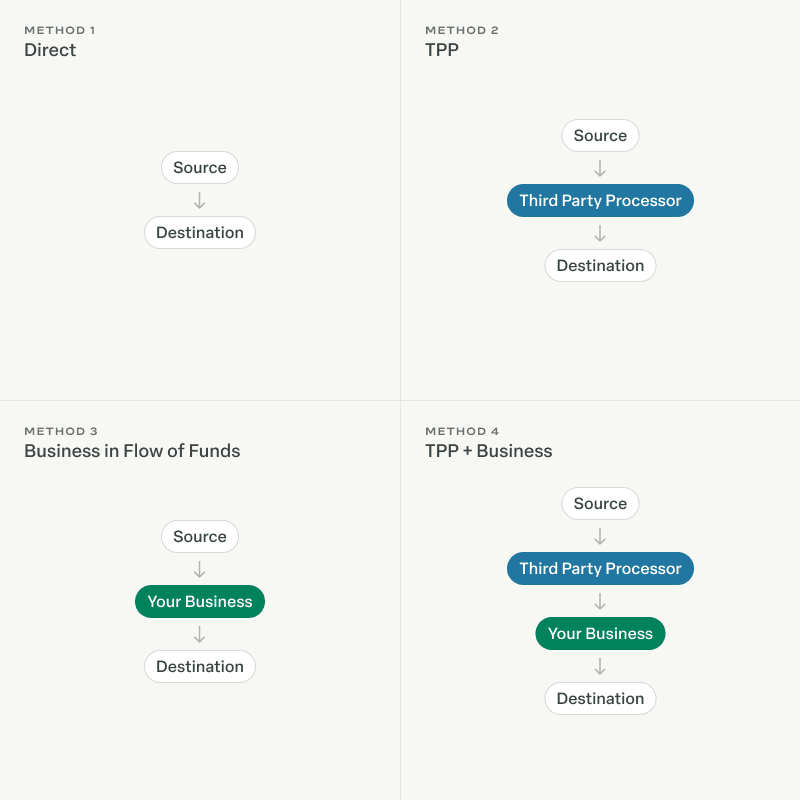

When thinking about the flow of funds, we can generalize different flows into four methods. This allows you and banks to classify the “hops” the money takes from the source to its ultimate destination. In its simplest form, this looks like the following:

While on the surface, this appears simple, it can quickly become challenging to understand, given how different business models, banks, and payment methods can affect the flows. To illustrate each method, we’ll use the example of an invoicing platform for freelancers.

Let’s call our invoicing platform, Invoiceable; this is “Your Business.” Freelancers use Invoiceable to send invoices to their Clients, who pay those invoices. In our diagram, the originator of the payment is the Client; therefore, the Client is the “Source” and the Freelancer is the “Destination” for those funds. Let’s see how this works.

Method 1: Direct

In a direct approach, money flows directly from the Source to the Destination. In this case, Invoiceable is not in the Flow of Funds. Invoiceable is simply providing the invoice but not processing any payments directly. Perhaps Invoiceable is displaying the Freelancer’s bank account information on the invoice for the Client to pay on their own.

Given this Flow of Funds, there is virtually zero risk or liability to Invoiceable. Invoiceable is never touching the money, and therefore they are not liable should the Client issue a return. The downside is Invoiceable won't have any insights into or control of the transaction. This will limit the amount of data your business has to enrich your platform and user experience, which could result in churn from the platform. It may also limit revenue opportunities, if you were gaining revenue through a transaction fee model.

Method 2: Third Party Processor

In some cases, money moves through a third party processor, who will temporarily hold the funds in a separate account while a transaction is being processed. This adds another “hop” in the flow.

Imagine Invoiceable has a “Pay this Invoice” button, which collects the Client’s banking information and initiates an debit from the TPP (not your business). The TPP will then later transfer that money to the Freelancer (less your business’ fees).

The key benefit of this method is reduced liability. These liability benefits are typically seen if the TPP has a strict compliance program, requiring them to limit amounts transferred, verify identities, and ensure that the originating account can cover the cost of the transaction. However, because the third party processor takes on this liability, there are often fees associated with using one. Additionally, the fact that they hold funds, means the payment will take longer to settle.

It’s important to note that a TPP will legally hold Invoiceable liable should the Client issue a return; maybe they were unhappy with services rendered and want their money back. If the Freelancer won’t return the money to the Client, Invoiceable will be liable for the funds, even if the only money that may have touched your account were the fees. Should the TPP find they cannot get back money from the Freelancer, they may withhold it from your future payouts—or worse, shut you down.

Method 3: Business in the Flow

This has the same amount of “hops” as Method 2, but instead of a TPP in the middle of the source and destination, it’s Invoiceable. The “Pay this Invoice” button on their invoice will collect the Client’s bank information, but this time Invoiceable will directly debit the Client’s bank account into Invoiceable’s bank account. When the funds settle in Invoiceable’s bank account, they’ll credit those funds, minus fees, to the Freelancer.

With the business directly in the flow of funds, the business is liable for any risk in that transaction. Invoiceable’s business model is pulling money from Clients, then pushing that money to Freelancers. There are two transactions here, the more risky being the “pulling,” or debiting, of the Client. Crediting Freelancers is not considered as risky because most people are not unhappy when you unrightfully give them money.

It’s important to accurately assess this risk. Let’s assume that Invoiceable’s Clients are all Fortune 1000 companies. Generally, you would not be worried about these companies paying their invoices. For this reason, you would likely assess your flow of funds as “low risk.” That means you can provide a compliance program, fund seasoning scheduling, and limits tailored to that risk profile.

This is inherently different from the TPP, who sees you as one of many businesses they support. They have their own compliance programs they maintain, perhaps forcing limits, lengthy payment schedules, and other requirements on you. So even though you sit in the flow of funds and assume all liability and risk of the transaction, you are also in full control.

That’s one of the major benefits of this approach. You can easily design your own compliance program (using tools like Modern Treasury or your own logic) to match the risk profile of each counterparty you interact with.

Another major benefit is cost. Typically, you will pay a fixed amount (on the order of cents to the dollar) which will vary by bank and payment rail. Most TPPs charge a high percentage fee for just the transaction alone. One reason for the high fees is how TPPs view risk. Given they have multiple customers across many different verticals, they must essentially average the risk of everyone together. They don’t always know which businesses are more risky.

The final benefit is a completely custom flow of funds, with the only restrictions applied to you by the bank. Sitting in the flow of funds gives you the most control over user experience, payment limits, and timing.

Method 4: Third Party Processor + Business

This model is similar to Method 2. The same issues apply, but in this case it can be more financially risky given the TPP first sends money to Invoiceable, which is later transferred to the Freelancer.

Should the Client issue a return against the TPP, the TPP will immediately issue a return against your bank account. The return will cost you money, and you will have to cover the balance should you have already transferred the money out to the Freelancer.

In some cases, TPPs may only offer Method 2 or Method 4 based on their agreements with their banking partner. For example, they may be forbidden to hold funds on behalf of a customer’s customer or be restricted to only paying out verified direct customers.

Summary and Next Steps

So how risky is it to sit in the flow of funds? The answer is “it depends.” Just like the flow of funds, it depends on your business, your products, why you’re moving money, the parties involved, and more.

The good thing is that you know your business best, which means that you know better than anyone how to de-risk your money movement. You can do so by designing a compliance program and flow of funds to meet your needs. It’s never zero risk, but for many businesses sitting in the flow of funds gives them greater control, better economics, and the ability to scale while easily mitigating risk.

It may seem overwhelming, because there are many risks and benefits to weigh when deciding whether or not your business should be in the flow of funds. If you want to talk through your options, drop us a note to get in touch.